Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Spotify | TuneIn | RSS

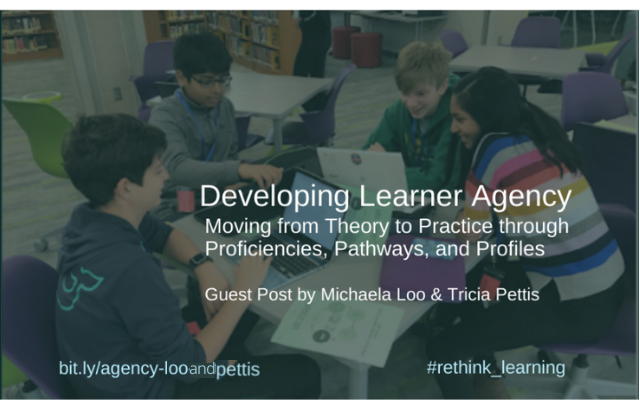

Moving from Theory to Practice through Proficiencies, Pathways, and Profiles

Four years ago, we attended the Edina Summer Institute where Barbara Bray was sharing her expertise in personalized learning as the keynote speaker. She struck a chord with us on many levels that day but when she said, “Teachers are doing all the work…” our trajectory as teachers immediately changed. After her keynote, we set a goal. We planned to personalize our class one unit at a time, and that is exactly what we did.

As we embarked on our personalized learning journey, we would never have imagined that a pandemic would have us all teaching and learning from home with very little lead time to prepare for this drastic and urgent shift. What quickly became clear was the optimal position our learners were in from the onset. Our gains in establishing systems and supports around personalized learning as instructional coaches and classroom teachers became levers we accessed to design an immediate response to teaching during a pandemic. Because our learners experienced opportunities to control, engage, and reflect in the learning process, they were able to capitalize on their established agency.

There are countless definitions of personalized learning. We define personalized learning as three interrelated layers that involve:

- Placing learners at the center where multiple pathways are possible to develop essential skills, and competencies.

- Guiding individuals to become agents of their learning through goal setting and reflecting on the learning processes.

- An active method where educators recognize the need for flexibility around pace, content, style, skill, background knowledge, location or some other learning dimension.

Currently, we are personalized learning coaches and classroom teachers at South View Middle School in Edina, MN. South View Middle School, hosts multiple site visits and professional development training for personalized learning. When we reflect on the momentous growth around personalized learning in our school, we relate it back to two things: updated systems and job-embedded supports. Building systems that back effective and responsive teaching is essential. Establishing ongoing supports that remove barriers for professional growth (i.e. time, resources, strategies) are critical.

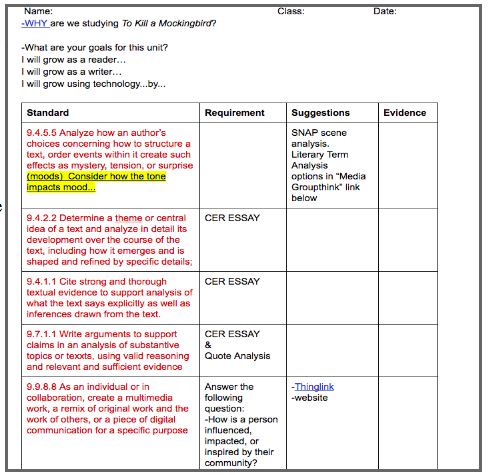

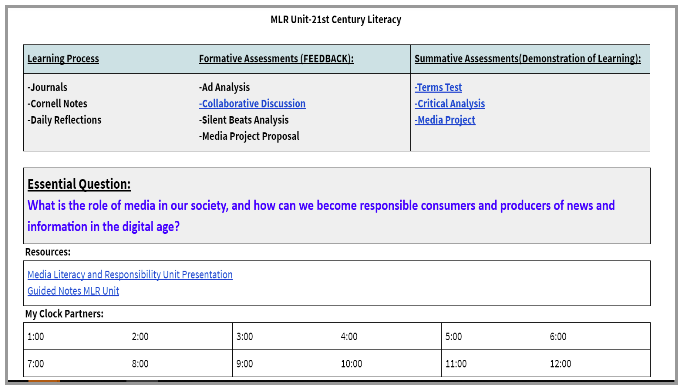

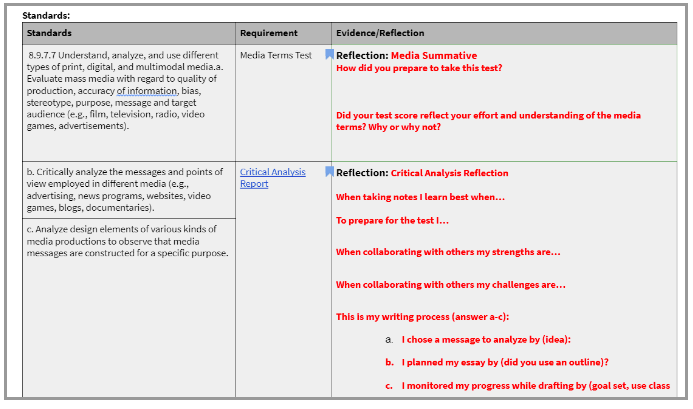

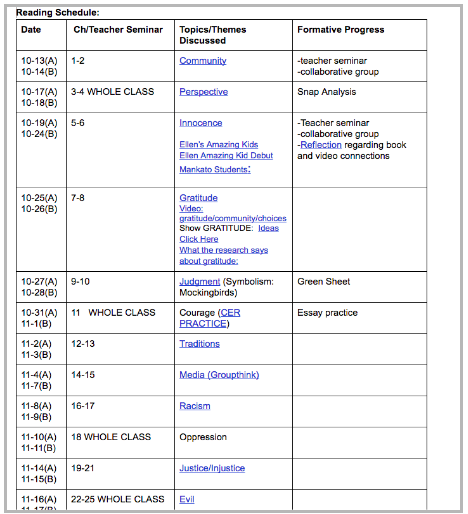

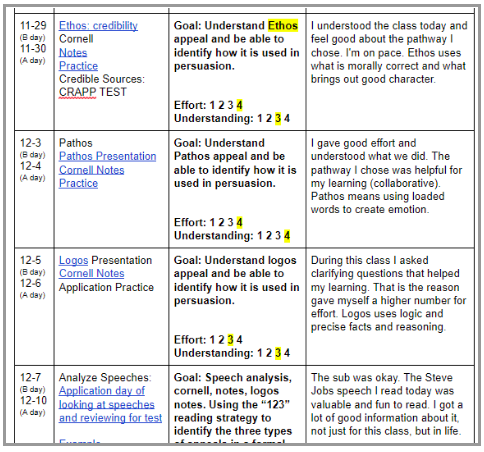

One system we constructed in order to personalize the learning process was designing a school-wide unit guide accessible to any content area. The idea of the unit guide is to create a template with three key components that any teacher can adapt for their courses. The three components are the 3Ps, proficiencies, pathways, and profiles. The unit guide is a simple Google document that is shared with learners via Schoology or Google Classroom. The general template of the unit guide outlines the learning targets and standards (proficiencies), lays out the pacing of content (pathways), and gives learners a place to reflect and track their learning (profiles). Adopting the unit guide ensures each student has their own copy of a resource that provides consistent support for their learning experience. Further, the guide gives learners a foundation for which they can begin navigating and controlling their learning choices. When introducing the unit guide to learners we asked the question, “What is the purpose of this document?” To which they responded, “To track our learning, to know where we are going, to have resources…”

Once we transitioned to distance learning we were still able to use the unit guide in the same way we did while we were in the classroom together. Learners knew where to find learning targets, set goals, access key resources, seek feedback, and reflect. Learners reported that their unit guides were extremely helpful, especially when many other elements of their school experience were dismantled and unpredictable. The unit guide offered learners a connection to their agency because they could see what was coming next, they knew how to locate all of their resources and assignments, and they could demonstrate their learning through ongoing reflection.

Proficiencies

At the start of a unit of study, we begin with the “why” and show the competencies, standards, or proficiencies that learners will work toward meeting. As Dr. Jim Rickabaugh says, “If one starts and stays with the why, this opens the flexibility for the how.” To form the foundation of the ‘why” for learners, we develop an essential question based on course standards. The unit guide maps out the required summative (“final” assessments that measure competency), that all learners must meet in order to demonstrate proficiency. Beginning each unit with an essential question every learner will address is a great place to incorporate voice and choice. A well-written essential question allows the learning to be connected to task performance. A task performance calls for the application of knowledge and skills, not just recall or recognition is open-ended and typically does not yield a single correct answer. Also, it establishes a novel and authentic context for performance and provides evidence of understanding via transfer.

When considering the ongoing assessment of learning, traditionally teachers create projects or tests for learners to complete. Teachers put an ample amount of time and creative thought into designing these types of completion assessments. As responsive educators, we need to ensure that the teachers are not doing ‘all the work’ as Barbara Bray points out in her invite to rethink how teachers design instruction. In other words, we need to develop learner capacity in ways that assure the cognitive load is carried by the learners.

As Zaretta Hammond states in her book, Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, “Our ultimate goal as culturally responsive teachers is to help dependent learners learn how to learn. We want them to have the ability to size up any task, map out a strategy for completing it, and then execute the plan.” (Hammond 2015). While we still have assignments that all learners complete, such as essays (literary analysis, expository, and narrative), we also design experiences that allow learners to dictate how they will demonstrate meeting a standard. This invite allows the learner(s) to express original thought, refine critical thinking skills, seek solutions, and grow in learning independence. Most importantly, this allows learners to tap into their passions and interests. We have seen learners more excited, engaged, and motivated when they have an active role in constructing their own summative (assignments that measure mastery of a standard). And we have witnessed individuals stretching themselves further than they imagined, thus enhancing their self-efficacy.

Consider the following example for a unit where the novel, To Kill a Mockingbird serves as the vehicle for learning. For one standard, we have learners complete a literary analysis around the evolution of the theme (learners chose the theme). The analysis is a staple and it’s a common summative each learner must accomplish. Learners are also asked to meet the standard of 9.9.8.8 As an individual or in collaboration, create a multimedia work, a remix of original work and the work of others, or a piece of digital communication for a specific purpose. They need to answer the question, How is one inspired, influenced, or impacted by their community? (there is that “why” again!). Learners are able to express their understanding through this choice and they welcome this opportunity. We encourage them to consider their personal passions around elements of a community be it volunteering, sports, environment, literacy, music, and art (just to name a few) and incorporate them into their learning. Structuring a unit in this manner resulted in authentic, meaningful projects full of inspiration, simply because we tapped into one of the most underutilized resources in classrooms today, the learners themselves.

Pathways

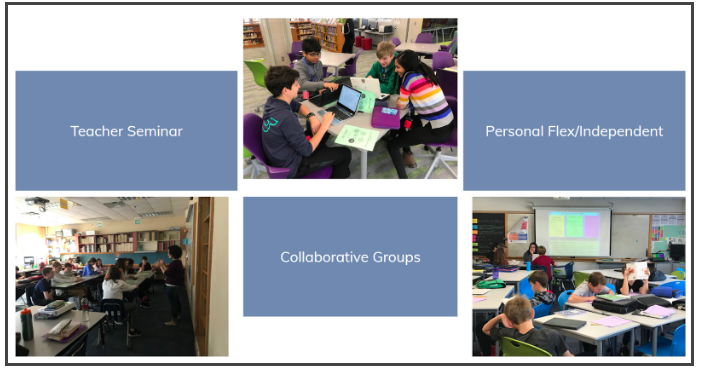

We view personalized learning as a verb, an active method of best practice that puts the learner at the center of instruction. Thus, we are compelled to use a variety of strategies with multiple pathways designed to meet the needs of all learners. Once the standards or learning targets are determined, different avenues for learning can be established. The body of the unit guide is a pacing guide that allows learners to have access to the content and resources with live links or directions to drive the learning which allows learners to engage with the materials in different pathways.

While there can be many learning pathways, our school landed on creating norms and common language around teacher seminars (direct instruction with the teacher), collaborative groups (2-4 people working together on a common goal), and independent flex. At the start of a school year, each grade level spends time discussing, practicing and naming each pathway. Naming, practicing, and reflecting on the effectiveness of each learning pathway engaged the learners in the learning process. They could choose which pathway was best for their learning and be in control of the pace. Once again, this training in learning pathways and common language made the transition to distance learning easier for learners and staff. Teachers began to offer teacher seminars via Google Meets and breakout rooms via Schoology for peer collaboration. Since learners had experienced different learning pathways, they were able to better understand and handle not having a teacher physically present, and alongside them to learn.

When we first started to personalize and offer choices in learning pathways, we were often questioned by fellow educators working in other schools. We would be asked by fellow teachers and parents alike, How can you trust that kids will make the right choices for their learning? That question and the concerns that come with it, expose a glaring disconnect in education today. If educators are not preparing and allowing learners to have a choice in their learning, and if we aren’t prioritizing ways to build learner agency, then we are doing our kids a tremendous disservice. Learners develop independence, self-confidence, and ownership if we set the conditions where they have more voice and control in their learning processes. Fast forward to COVID19, that ownership allowed learners to transition to distance learning more confidently because they knew how they learned best, they experienced advocating for their needs and they believed in their ability to take even more ownership and control.

A teacher’s role during distance learning is not any less important than in a more traditional setting. In fact, we would argue that the teacher’s role in guiding, modeling, and monitoring the learners so that they understand what choices to make and how those choices impact the learning is even more significant. The teacher role in this capacity is even more necessary and meaningful to learners. When the purpose is clear (connected to standards/learning targets), formative assessments are used to open channels to feedback, and reflection is ongoing, the learners can be trusted with making informed choices alongside their teachers.

We guide learners in knowing what learning pathways to choose through timely, specific, and actionable feedback. Like many schools, in the past, our traditional practice around feedback consisted of points/grades for formative (daily) work with more thorough comments given on a summative (final) assessment. Teachers have now reversed that order and invested more time offering feedback in the form of comments on the formative work and only a final score on summative work. John Hattie (2007) places feedback in the top ten influences on achievement. There is variability when it comes to feedback, so teachers and students need to understand which feedback is most effective. “Feedback should, therefore, be useful when it helps students navigate this gap, by addressing fundamental feedback questions including ‘where am I going?’, ‘how am I going?’ and ‘where to next?’(Hattie, 2007, p.3). Thorough feedback in the formative process informs learners what they know, along with direction for an appropriate pathway to continue learning.

Reflection (Profile)

Another critical lever to put learners at the center is the implementation of a learner profile. For years teachers have been compiling data and information on learners to guide instruction, but how much of that information drives the learning? If we want learners to be able to have voice and choice in their learning, they have to understand how it is they learn best, their strengths and weaknesses, and how to apply their skills and interests to their learning experience. The final component of the unit guide is a space for learners to track, record, and reflect on their learning process. Asking learners to reflect regularly, reminds them to focus on the learning process rather than striving to be compliant. Everything we do is an opportunity for learners to discover something about themselves. Learners use the pacing guide to reflect on the feedback they receive from the teachers and peers and document what their next steps should be.

“When kids have an opportunity to reflect on how they learn, this can be a way for them to explain who they are and how they learn and to have their learning validated.” (Bray & McClaskey 2015). During distance learning, we begin each class by setting a goal and at the end of class. The learners are prompted to reflect on that goal, the choices they made in pathways, and what learning occurred. The learners also linked any evidence of their learning in the reflection box so we could monitor their progress and provide feedback. Reflecting on the unit guide made it easier for learners to track teacher feedback and use it to plan for the next steps. This consistency shows learners that by engaging in this process they are continuing to grow their skills, to self-regulate, and be in control of their learning.

Even in the face of uncertainty, there is no looking back.

While none of us could have predicted or fully prepared for a worldwide health pandemic that would close school buildings, we do believe our efforts around personalized learning positioned our learners for an easier transition to distance learning. Our pillars of personalized learning; proficiency (process over content), pathways (multiple ways to engage in learning), and profile (reflection over compliance) prepared learners to be engaged, independent learners. The agency and confidence that our learners have built through choice have empowered them to assuredly and confidently continue their learning outside of school and beyond.

As our school considers what learning may look like in the fall, one thing is certain, the unit guide will serve learners well whether they are in the classroom or learning remotely. The unit guide provides meaningful consistency for how learners engage and reflect on their learning. In turn, teachers are able to build in ways to make personal connections beyond greeting learners at the door or validating learners on site, because they aren’t spending significant time building a system for learning.

Barbara Bray’s keynote gave us a new lease on teaching and for that, we are forever grateful. She inspired and challenged us to change our practice in order to take the theory of learner empowerment and put it into action. Finally, Barbara Bray gave us an on-ramp to tap into what Dr. Jim Rickabaugh says is the most important resource in the classroom today, the learners themselves. We haven’t looked back.

*****

Michaela Loo, Personalized Learning Coach, Teacher, and Consultant, educatorsignite@gmail.com, @MichaelaMLoo

Michaela Loo, Personalized Learning Coach, Teacher, and Consultant, educatorsignite@gmail.com, @MichaelaMLoo

Michaela is a personalized learning coach, teacher, and consultant in MN. She supports the implementation of learning processes that offer multiple pathways and allow for continuous reflection on personal growth against core competencies. She leads professional development and site visits on personalized learning for teachers and educational leaders from multiple school districts in MN. She is in her 17th year as a proud educator and teacher leader.

Patricia Pettis, Personalized Learning Coach and Teacher, educatorsignite@gmail.com, @triciapettis10

Patricia Pettis, Personalized Learning Coach and Teacher, educatorsignite@gmail.com, @triciapettis10

Patricia is a personalized learning coach, teacher, and consultant in MN. Patricia works with teachers, administration, parents, and learners on implementing personalized learning practices that engage learners in the learning process. Patricia leads professional development training on offering multiple pathways for learning through goal setting, feedback, and reflection. She empowers learners to develop their skill sets and become agents of their learning.

Follow both of their journeys at the Team Teaching Sisters website:

http://sistersteamteaching.blogspot.com

******

References

Belfield, C. (2015). The Economic Value of Social and Emotional Value. Online. Available. March 5, 2020. https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/rulesforengagement/SEL-Revised.pdf

Bray, B. (2020) Define Your Why: Own Your Story So You can Live and Learn on Purpose. Alexandria, VA. Edumatch Publishing.

Bray, B., & McClaskey, K. (2015). Make Learning Personal: The What, Who, Wow, Where, and Why. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Hammond, Z. (2014) Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Hattie, J. (2007) The Power of Feedback. Online. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3102/003465430298487

Rickabaugh, J. (2016). Tapping the Power of Personalized Learning: A Roadmap for School Leaders. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

******