I have referred to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs for as long as I can remember. I learned about it as a way of looking at the complete physical, emotional, social, and intellectual qualities of an individual. It seemed obvious that this could be applied to education so I shared it during speeches, online, and in coaching. I never thought of where and how it came to be. I look back now and wish I had the curiosity and skepticism I have now and had done my research.

When I shared his hierarchy during a Twitter chat, my friend Ken Shelton @k_shelton sent me a direct message asking me if I had done any research on Maslow’s Hierarchy. I have but apparently not on the points he mentioned so he sent me this link http://bit.ly/maslow-blackfoot-connection that I shortened for you. I added other research I found at the bottom of this post.

The article Maslow’s Hierarchy Connected to Blackfoot’s Beliefs by Karen Lincoln Michel in 2014 opened my eyes and reinforced some of my own thinking about what motivates people. So a little history of Abraham Maslow as one of the founders of humanistic psychology is that “he generously borrowed from the Blackfoot people to refine his motivational theory on the hierarchy of needs.”

Maslow’s Motivation Theory

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a theory in psychology proposed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” in Psychological Review. Maslow subsequently extended the idea to include his observations of humans’ innate curiosity. Let me review with you what Maslow’s theory suggests. He illustrates that people are motivated by fulfilling basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing first which is at the bottom of the triangle. As you move up the triangle, the next need is safety and security, then love and intimacy, then self-esteem, and then at the top: self-actualization. This highest level is where people are self-aware and achieve their fullest potential.

“It is quite true that man lives by bread alone — when there is no bread. But what happens to man’s desires when there is plenty of bread and when his belly is chronically filled?

At once other (and “higher”) needs emerge and these, rather than physiological hungers, dominate the organism. And when these in turn are satisfied, again new (and still “higher”) needs emerge and so on. This is what we mean by saying that the basic human needs are organized into a hierarchy of relative prepotency.” (Maslow, 1943, p. 375).

What was and was not in Maslow’s Theory

In reading several reviews of the theory, there were critical evaluations of his findings. Maslow used limited samplings of self-actualized people including biographies and writings of 18 people he identified as being self-actualized. He used personal opinion which is prone to bias and reduces the validity of the data obtained. But that didn’t seem to matter to educators. If you do a search on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, you will see this 5 level version. There is a seven-stage and then an eight-stage model later developed during the 1960s and 1970s. [Source: Simply Psychology 2018]

Maslow’s work centered around the humanistic approach but he never created the pyramid. Many people may not realize that during the last few years of his life Maslow believed self-transcendence, not self-actualization, was the pinnacle of human needs. According to this article in Scientific American, a business management consultant created Maslow’s pyramid. [Source: Kaufman, 2019] In the 1950s, Douglas McGregor brought Maslow’s psychological work into management studies, and Keith Davis adapted Maslow’s idea to give weight to a fledgling field. In the 1960s, Charles McDermid promoted Maslow’s theory in pyramid form, as a tool for consultants. [Comment below: Alonzo Paz]

Blackfoot Nation translated from Siksika Nation

I received an email from Councillor Leon Crane Bear who is a member of the Siksika Nation (part of the Blackfoot Confederacy) located in Alberta, outside of Calgary in Canada where he gave me more information about the proper spelling (“Siksika” which translates to Blaackfoot). The Siksika Nation is a First Nation in southern Alberta, Canada. The name Siksiká comes from the Blackfoot words sik (black) and iká (foot), with a connector s between the two words. Siksika has a total population of approximately 7500+ members. Siksika are a part of the Blackfoot Confederacy which also consists of the Piikani and Kainaiwa of southern Alberta and the Blackfeet in the State of Montana. More information at Siksika Nation.

I received an email from Councillor Leon Crane Bear who is a member of the Siksika Nation (part of the Blackfoot Confederacy) located in Alberta, outside of Calgary in Canada where he gave me more information about the proper spelling (“Siksika” which translates to Blaackfoot). The Siksika Nation is a First Nation in southern Alberta, Canada. The name Siksiká comes from the Blackfoot words sik (black) and iká (foot), with a connector s between the two words. Siksika has a total population of approximately 7500+ members. Siksika are a part of the Blackfoot Confederacy which also consists of the Piikani and Kainaiwa of southern Alberta and the Blackfeet in the State of Montana. More information at Siksika Nation.

In 1938, Abraham Maslow visited the Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation. There is evidence of Maslow’s work there with a link to an archival photo that places Maslow on the Blackfoot reserve at that time, and a link to more information on the Blackfoot people’s influence on Maslow.

Karen Michel interviewed Dr. Cindy Blackstock who is the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada about Maslow’s connection to the Blackfoot Nation.

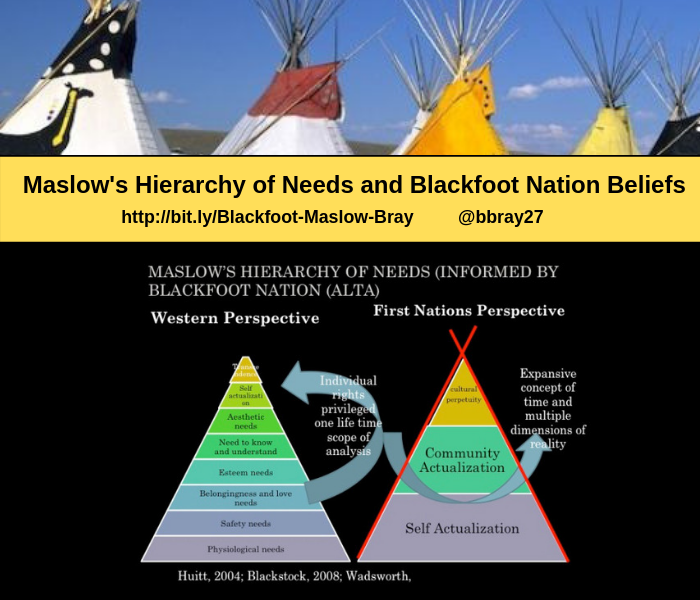

The Blackfoot belief is not a triangle. It is a tipi where they believe tipis reach to the sky.

Self-actualization is at the base of the tipi, not at the top, and is the foundation on which community actualization is built. The highest form that a Blackfoot can attain is called “cultural perpetuity.”

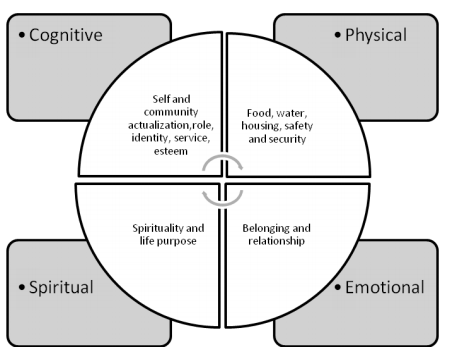

Blackstock shared in her research, the breath of life theory that was interpreted by Native American child welfare expert Terry Cross in the relational worldview model (Cross, 1997; Cross, 2007). The principles are categorized into four domains (cognitive, physical, spiritual, and emotional) of personal and collective well-being:

Cross presented in 2007 at a keynote that Western views are linear and native and tribal views are relational:

- Fluid, cyclical view of time

- Each aspect of life is related

- Services aim to restore balance

- Interventions may not be directed at “symptoms”

- Underlying question is “how?”

Blackstock explained cultural perpetuity as something her Gitksan people call “the breath of life.” It’s an understanding that you will be forgotten, but you have a part in ensuring that your people’s important teachings live on.

Blackstock referred to research by Ryan Heavy Head and Red Crow Community College on the Blackfoot approach to science was funded in 2005 through an SSHRC Aboriginal Research Grant that he shared in a post in 2007, How First Nations Helped Develop a Keystone of Modern Psychology.

“Blackfoot people have their own systems for developing new knowledge in traditional ways,” says Ryan Heavy Head, one of the researchers at Red Crow. “It’s less focused on categories and more interested in how things come together.”

As illustrated in Blackstock’s diagram below, self-actualization was on the bottom, as the starting point. The self was only the beginning for the Blackfoot, who placed community actualization and cultural continuity above the individual. Maslow’s western lens flipped it around to prioritize the individual. [Source: Lincoln Michel, K. 2014]

The image used in the graphic above shows basic differences between Western and First Nations perspectives, as presented by the University of Alberta professor Dr. Cindy Blackstock at the 2014 conference of the National Indian Child Welfare Association.

References

Blackstock, C. (2011) The Emergence of the Breath of Life Theory. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, Volume 8, Number 1 (2011) Copyright 2011, White Hat Communications.

Cross, T. Through Indigenous Eyes: Rethinking Theory and Practice. (2007) Keynote Address.

First Nations Education Steering Committee https://www.fnesc.ca/

Heavy Head, R. (2007) How First Nations Helped Develop a Keystone of Modern Psychology. Social Science and Humanities Research Council. Online 3-10-18.

Kaufman, S. (2019) Who Created Maslow’s Iconic Pyramid? Scientific American. 4-23-19.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-96.

McLeod, S. (2018). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Online. 3-10-19. Simply Psychology.

Michel, K.L. (2014) Maslow’s Hierarchy Connected to Blackfoot Beliefs. Online 3-10-19

Siksika Nation on Wikipedia

Siksika Nation website

****

Interested in checking out more of the Rethinking Learning podcasts and reflections, click on the podcast tab at the top, the logo below, or go to https://barbarabray.net/podcasts/

For more information about Barbara’s new book, Define Your WHY, go to this page or click on the image of the book for resources, questions, and links.

This is a fascinating article with some thought-provoking ideas. Unfortunately, most of the links no longer function, or lead to unrelated websites. Repair of these would be very appreciated!

Thanks, Katie! I appreciate you letting me know that some links no longer were working. I believe I fixed all of them now. Let me know if you notice anything else.

Barbara

[…] from the Blackfoot belief, as described here by Barbara Bray, the notion of self-actualization (one which Maslow culturally appropriated) is not a triangle but […]

[…] B. (2019, March 10). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation Beliefs. Retrieved from […]

[…] B. (2019, March 10). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation Beliefs. Retrieved from […]

Wonderful insight. We have developed two schools that started by addressing the bottom two triers of Maslow (which Maslow didn’t create: In the 1950s, Douglas McGregor brought Maslow’s psychological work into management studies, and Keith Davis adapted Maslow’s idea to give weight to a fledgling field. In the 1960s, Charles McDermid promoted Maslow’s theory in pyramid form, as a tool for consultants.)

That being said our model 14 years later is called the Collective Care Continuum (C3). The only way we could meeting each individual student’s needs was as a collective and addressing the communities’ needs and deficits. It does take a village to raise a child. From this point forward I will be acknowledging the influence of the Blackfoot Nation’s influence. I would love to talk more on how our schools developed a whole community involvement, in supporting student learning, that goes beyond the high school diploma. Our students give back and share with their community in a similar way of “the breath of life.” They say our schools sees them, hears them, values them, because we value connections and relationships over academics, which enables them to tell their stories of who they are with pride and love (self-actualization).

Alfonso,

I’m interested in learning more about your model, Collective Care Continuum (C3). Please share a link and let’s connect.

Barbara

[…] Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation Beliefs […]

Hello, thank you for this article. One of the things that my cursory online research shows is that Maslow never presented his work with the triangle. So how does this impact the “idea” that he stole the visual and turned it upside down. His model makes sense for a culture that is individualistic and self driven unlike communal cultures like the Blaackfoot nation. I am grateful for the teepee image. I am Yoruba from Nigeria and it aligns with our system of always upholding the whole. Perpetuity would be a person becoming a good ancestor when they die. I am not sure I buy that Maslow stole the Blaackfoot nation idea though. Thank you for this write up.

[…] — Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation Beliefs […]

[…] B. (2019, March 10). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation Beliefs. […]

[…] Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Blackfoot (Siksika) Nation Beliefs: If this is new to you, please read the excellent summary by Barbara Bray of how the model is rooted in Blackfoot beliefs and Maslow’s version whitewashes and erases this origin. […]