Nicole Biscotti tells an amazing story of the desert valley and its history. I’m honored to host her story on this site. Nicole takes you on a journey with the original owners, the settlers, and the desert today with the border wall.

The Desert Valley That Feeds Us

This article was researched, and all of the photos were taken, and written while living in Mexicali and teaching Spanish in the Imperial Valley. As I drove through this area crossing the border to go to work every day, I became intrigued about this unique international community that has now found itself square in the center of the water wars. The intention of the article is to provide context to the historical, geographical, and economic forces that have made it both possible and unsustainable, for a desert valley to provide a large part of the nation’s fruits and vegetables. It’s focused on telling the interwoven stories of the land and its people. The ironies that have led to an agricultural empire both providing a large share of the nation’s produce and using more water than two states combined from a drying river are also highlighted.

Part 1: The Original Owners

Where the Rocky Mountains fade into hills of boulders they are met by a fertile valley in the midst of a desert. Its emerald green fields against a backdrop of barren mountains and sand dunes are unknown to most of the country. In their haste to get between big cities, hordes of travelers on Highway 8 pass by it every day without so much as a second glance at the valley that fills their tables with fruit and vegetables in the winter months.

Interstate 8, Juan de Bautista De Anza Historic Trail, Kumeyaay Freeway

The scorching desert sun both subjects the people of the valley to extreme temperatures and provides ideal conditions for two growing seasons. The arid land is rarely blessed with enough rain to form a puddle yet there are stately rows of alfalfa, lettuce, melons, carrots, and many other fruits and vegetables under sprinklers as far as the eye can see. Once harvested, they are sent all around the United States and even to countries far away. It doesn’t matter that there’s hardly any water, the valley’s bounty is possible because of an impressive feat of agricultural engineering accomplished 100 years ago that remains impressive today.

The Quechan diverted the river to feed their crops

The original owners of the valley have known how to find water to grow the food they needed to survive there for over a thousand years. The Quechan diverted the river to feed their crops and used its flooding patterns to grow melons, pumpkins, beans, and corn. The Kumeyaay moved with the seasons and traveled on trails that are now covered with asphalt and called highways. They built dams with rocks in streams to collect water and carefully protected it from the sun with ollas. The Cocopah dug canals to water their fields from the river and collected the little rain that fell in basins.

A long time ago, five years after the United States rose up against England to become the “land of the free”, the Quechans rose up against the Spanish who had moved into their land and began calling it Mexico. They had grown tired of the Spaniards’ oppressive rule with their forced religion and liberal use of punishments. They waited for just the right moment when there were fewer Spanish soldiers and used their numbers to their advantage. It was a bloody fight; they clubbed the four priests at the mission to death and threw them over the hill. Many Quechan lost their lives as well. Other battles followed but the Quechans managed to thwart the Spaniards’ plans for expansion in Alta California and remain free in their land — for a short time. After the Spanish left, the settlers came in greater numbers and were much more determined to conquer the desert.

St. Thomas Yuma India Mission which replaced the original Purísima Concepción Mission

Part 2: The Valiant Settlers Arrive

Almost two hundred years ago settlers came and called the land around the valley the United States. By the arrival of the settlers, the majestic valley that now feeds the nation was known to claim many lives. De Anza dreaded crossing the windswept valley and called it “la jornada de la muerte” (the journey of death). The soldiers under General Kearney, the Mormon Battalion, those with Butterfield Stages on their way to San Francisco, and the gold miners in the mid-19th century all had a justifiable fear of the valley. There were reports of many deaths and sightings of human remains, even years later. Mr. Thing, the first noble settler of Calexico, found hundreds of skeletons on his land. The desert along the wall that runs through the valley is still known as “El Camino del Diablo” (The Devil’s Way) for all those who lose their life attempting to go from one side of the valley to the other without the government’s permission.

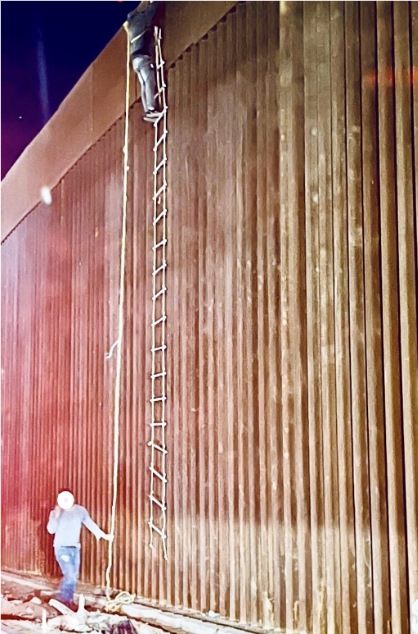

The Border Wall in the Desert

Although many others had rushed past this parched desert in pursuit of gold, the settlers knew that the barren valley itself was far more valuable. The treasure of the valley is found in the land that was left by the river and the sea. Its soil is rich with the nutrients of millions of years in the sediment of the ocean floor from the time when the Gulf of California covered the valley. The receding gulf left low-lying flat land ideal for farming and irrigation. The Colorado River then brought precious alluvial deposits for thousands of years as it meandered back and forth carving out the Grand Canyon.

An aqueduct from the Colorado River brings water to the Valley

Inspired by the abundance possible if they had water for farming, the settlers undertook an epic feat of engineering to summon the Colorado River to the great valley. Eventually, even the river would bend to their mighty will and travel through a complex system of aqueducts and canals for 80 miles as it passed through Mexico and then flowed to their fields. As the water poured into the valley so did more valiant settlers who founded the proud cities that still stand today.

Calexico

Workers from Mexico, China, and nations all over the world came to help the distinguished settlers to bring the river water and the railroad through the valley. Many never left; some decided to stay and settle in the valley, others went to Mexico to escape persecution, and many lost their lives doing dangerous jobs for low wages. The settlers learned about gathering water from the original owners of the valley and based their system on their ways. Although much has changed, much has remained the same such as the zanjeros who continue to skillfully direct the river’s waters just as they have since the land was called Mexico.

The railroad connects the valley

When a design flaw caused a flood that almost destroyed everything they had built, the independent settlers united to quell the river. The railroad ultimately saved the valley in ’05 from flooding and the check in the mail from the government never did arrive. Farming had to be learned over from the very beginning under the unforgiving desert sun with the river’s salty water. More settlers failed than succeeded. Through the settler’s resolve, 450,000 acres of some of the most productive farmland in the world were established and an agricultural empire was born. Some people in the valley today are descended from those distinguished few who persevered and prevailed. They steadfastly remain by adapting and innovating with agility to challenges unique to their desert valley. Many others sold their land to large companies from places far away.

Fields in the midst of the desert

Part 3: The Desert Valley Today

Today where the fields end, there is an imposing wall. If you stand near it, you can see a large city on the other side through its wide slats. It has universities, factories owned by people from the United States, and many restaurants and entertainment venues. Some people travel back and forth, even daily, for work and school. Many people in the big city can only peer at the United States through the slats in the wall though because they are not granted permission to cross to the other side. Everyone who lives on the side of the valley called the United States can go into the side of the valley called Mexico though.

People line up for hours to cross the border daily

There was a time, long ago when there was no wall at all and people walked back and forth without much thought. Even farther back, before anyone can recall, the whole valley was called Mexico. Many of the ranchers who lived there had a highborn ancestor and were given their land by the Spanish crown from when the land was ruled by the Spaniards and called Alta California. When the valley became part of the United States the people living there understood that they could remain in their homes and continue with their way of life. They spoke a different language though and didn’t understand manifest destiny or anticipate the abuse or the ways they would be excluded from the American dream.

People meeting to talk through the wall

Many workers are needed to harvest the valley’s great bounty, the majority of which have always come from the other side of the wall. Their labor is backbreaking and all too often their compensation has been low wages and poor conditions. Some are able to go home across the wall each night and others cross not knowing when they can return but hoping to provide for their family at the cost of leaving them behind. Workers who don’t have the government’s permission continue to cross the wall anyway despite the lives claimed by its height, the canal that brings water to the valley, and the harsh desert. They come to toil under the unrelenting sun while many sons and daughters of the valley leave for big cities with more opportunities.

The Border Wall

Although the people of Mexico weren’t given a chance at the American dream when they found themselves living in the United States, many people living in the grand valley today are the children and grandchildren of those that crossed the wall to work. More people than not have last names brought from Spain and the melodic sound of the Spanish language has always been heard in the valley from the days when it was called Mexico to the present.

Downtown Calexico and Mexicali through the Border Wall

Today the settlers’ billion-dollar legacy is under a threat they never foresaw. Large cities have grown in the once almost inhabitable West. They also use the river’s water and now it’s running out. Even with a first claim, there’s only so much water to be taken from a drying river. As the people of the valley found ways to save their precious water, their farms no longer had enough runoff to fill their small seas. As the sea began to evaporate, the desert winds blew pesticides through the valley and the children and elderly began to get sick.

Although the Quechans, the Kumeyaay, the Cocopah, and the others no longer own all of the lands, they could teach us how they farmed for a thousand years without drying the river or making people sick with polluted air. Sadly, many were driven out long ago and when those that remain raise their voices they are not loud enough to be heard. Meanwhile, the great valley continues producing fruits and vegetables for the nation and sending food to the world.

*****

Nicole Biscotti is a Momvocate, Educator, and Author whose focus is on the future of education as being informed by relevancy and the needs of our currently marginalized, under-supported learners. We have a lot to learn if we listen!

Nicole wrote I Can Learn When I’m Moving: Going to School With ADHD http://bit.ly/icanlearnwhenimove with her 9-year-old son from the unique perspectives of a child and a mother who is also a teacher. She has seen both personally and professionally how children struggle to be understood and how adults are often at a loss with how to handle the difficult behaviors associated with ADHD. She empowers parents and teachers to provide game-changing support for children with ADHD in school by sharing her and her son’s stories, along with researched-based strategies.

Nicole has also translated books into Spanish such as El Cuento del Perdón by Melody McAllister and Todos Pueden Aprender Matemáticas by Alice Aspinall. I Can Learn When I’m Moving: Going to School With ADHD is also coming soon en español.

Her next book, Invisible con ADHD: Real Voices, Real Policy for Latino Students is co-authored with Andrea Aguirre. They address the issues around the disproportionate lack of support that Latino children with ADHD are faced with. Through interviews with former students, educators in the United States and Mexico, and extensive research, they will offer educators a holistic view of the obstacles that currently stand in the way of protecting kids from poor outcomes as well as offering research-based solutions.

You can connect with Nicole at NicoleBiscotti.com on Twitter @BiscottiNicole or at IG @MeaningfulInclusionEdu.

Nicole blogs about her life as a border commuter at: https://medium.com/@labordervida and relevancy and meaningful inclusion in education at: https://medium.com/@BiscottiNicole

Podcasts with Barbara and Nicole

Rethinking Learning Episode #85 on Bridging Understanding

Rethinking Learning Reflection #14: Why I Can Learn When I’m Moving

Look for a new podcast “Real Talk with Barbara & Nicole” coming soon.

*****

Photos taken by the author.

The Imperial Valley in 1904 – San Diego history center: San Diego, CA: Our city, our story. San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. (2016, September 30). Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1976/january/imperial/

Southern California: Comprising the counties of Imperial, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, Ventura, Southern California Panama expositions commission, 1914. Imperial County California County History. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2023, from http://genealogytrails.com/cal/imperial/countyhistory.html

The Imperial Valley in 1904 – San Diego history center: San Diego, CA: Our city, our story. San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. (2016, September 30). Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1976/january/imperial/

Data Portal. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/

Morales, J. (2021, May 6). Oral history explores Imperial Valley’s black experience. Calexico Chronicle. Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://calexicochronicle.com/2021/05/06/oral-history-explores-imperial-valleys-black-experience/

Scalet, S. (2021, September 1). Sustaining the humanities in California’s Imperial Valley. The National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved April 25, 2023, from https://www.neh.gov/blog/sustaining-humanities-californias-imperial-valley

*****

Submission Notes:

Until now, my writing has been mostly specific to education issues. This work connects my undergraduate degree in Spanish Literature with my personal experiences. I wrote the book I Can Learn When I’m Moving: Going to School With ADHD (EduMatch Publishing, 2021) to raise awareness about ADHD from the perspective of a mother and teacher. I translated it into Spanish and it will be released in late 2023 in Spanish. At the present time, I’m writing “Invisible Con ADHD: Real Voices, Real Policies for Latinx Students” (to be published by EduMatch Publishing). I have also written numerous articles, blogs, forwards, and vignettes for other authors’ books as well as translated two children’s books. More details and links can be found on my website – NicoleBiscotti.com.